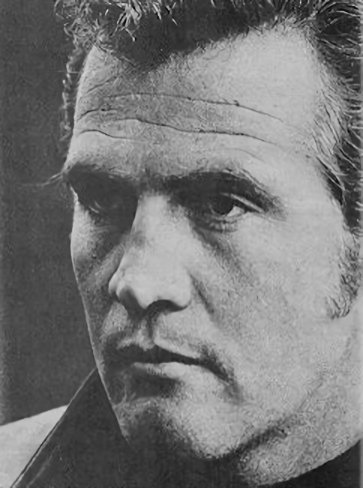

WHY BARBARA STANWYCK DISLIKES LEE MAJORS - & WHAT HE DID TO DESERVE IT

by Julie Jackson

Barbara Stanwyck, the fifty-nine-year-old movie star with the girlish waist and hair that turned prematurely gray thirty years ago, has little in common with the twenty-eight-year-old guy from Kentucky who plays here son the “The Big Valley” TV series. Of all the stars in Hollywood, the gracious, gallant lady who grew up an orphan on the streets of Brooklyn is perhaps best loved. Of all the young men and women with hands reaching for the next rung of the ladder and eyes focussed on the main chance, Lee Majors is perhaps the most disliked. “The only kind of love Lee knows,” says a member of the “Big Valley” organization, “is self-love. He treats members of the crew and extras – the unimportant people by Hollywood standards – as though they were less than human. Barbara Stanwyck would be kind and gracious to a visitor from skid row. Peter Breck and Dick Long are as courteous to the unimportant people they come into contact with with as they are to the important.

The extra with connections

“A few weeks ago a pretty girl was hired as an extra for one episode. This girl dates a man who has a technical job on the show. Between scenes she walked over to talk with him. Lee watched her for a while. Then he stalked over and interrupted their conversation. ‘Why are you talking to her?’ he asked the man. ‘She’s an extra.’

“A few weeks ago a pretty girl was hired as an extra for one episode. This girl dates a man who has a technical job on the show. Between scenes she walked over to talk with him. Lee watched her for a while. Then he stalked over and interrupted their conversation. ‘Why are you talking to her?’ he asked the man. ‘She’s an extra.’

“You want to know something? The girl was Sherry Smothers, sister of Tom and Dick Smothers. If Lee had known she was the sister of the Smothers Brothers, he wouldn’t have been so rude. In fact, he probably would have asked her to marry him, because he’s so impressed by anyone with connections.”

There are many kinds of love and many ways of failing at it. Barbara Stanwyck knows that. Lee Majors does not.

Each time Lee embarrasses his girl friend in an interview or uses her car to go out with another girl, he betrays her love for him. Every time he swings with a girl and reports the details to anyone who will listen, he betrays the privacy that is apart of love. And the understanding and brotherly love that people should have for each other escapes Lee entirely.

He was on location last spring, making his first motion picture, “Will Penny.” Lee Majors was not the star of the film. Charlton Heston was. As a courtesy, a car was provided for Charlton Heston. Because no car was given to him, Lee sulked.

The director and producer of the film made arrangements for four magazine photographers to drive up from Los Angeles to take pictures of the cast. When Lee was asked to pose, his answer was, “I won’t pose unless you put me on the cover.” The photographers tried to explain that they had no control over whose photograph would be put on the magazine covers. “Then I’m sorry,” Lee said, “but I won’t let you take pictures.”

One of the photographers looked hard at Lee. “Lee, you’re not really ‘sorry’,” are you?”

“No,” Lee admitted matter-of-factly, “I’m not sorry at all.”

The path of Lee Majors’ first two years in Hollywood is strewn with the bodies of people who gave him help, affection or devotion – and whom he then abandoned.

A photographer took dozens of pictures of the unknown boy from Kentucky in order “to give the kid a break.” Six months later the photographer couldn’t even get Lee on the telephone. A publicist befriended Lee and handled his public relations, even though Lee didn’t have any money to pay her. The minute he became successful, he fired her. A moderately well-known actress introduced him around Hollywood. He appeared to merely use her importance to get publicity.

From Barbara Stanwyck, Lee Majors could learn many things about love. He could learn first about “the feeling of benevolence and brotherhood that people should have for each other,” as Websters’ Dictionary puts it.

Several years ago on a boiling summer day, some of the grips working under the white hot arc lights on the Barbara Stanwyck film took off their shirts. An officious assistant director dressed then down, asking how they dared take off their shirts when they were in the presence of Miss Stanwyck.

“On a day as hot as this they can strip naked,” Miss Stanwyck said, and sent out for beer for the entire crew.

When the “Big Valley” series started, Barbara Stanwyck saw in Lee Majors, talent, ambition and a certain screen magnetism. She was as graciously willing to help him as she had been to help William Holden, Robert Wagner, and half a dozen other young men cast opposite her early in their careers. But Lee Majors did not respond with the gallantry of Holden (who stills sends her flowers every year as a token of his gratitude) or the charm of Wagner. Before a season passed, Lee had announced to the press that Miss Stanwyck was jealous of all the fan mail he was receiving.

Then he began to take advantage of his emerging “stardom.” He caused innumerable crisis.

The most generous interpretation of his gaucherie is that it came from his over eagerness to be successful: by the exhilarating effects of Hollywood sunlight on a Kentucky hill boy. “Missy” Stanwyck ignored his tactlessness when it was merely directed towards herself. But she refused to tolerate his lack of consideration when it affected the crew.

She gave him a bitter tongue-lashing in front of the entire crew. It included phrases like: “You have to learn to crawl before you can walk. Then, maybe you can run a little. You’re not a star yet. I am a star. Do you want to see what a star can do? One of us is going to get out of this television series and I don’t care which one of us it is!”

Lee’s agent made him apologize to Barbara Stanwyck a few days later. She accepted the apology. But Lee’s insensitivity had closed a door. He had lost for himself all the help and consideration that one of Hollywood’s great stars was offering him.

There are many kinds of love and many ways of failing at it. The child of Lee Majors’ first marriage is growing up in Virginia, and his memory of his father dims as the month pass. Barbara Stanwyck is permanently estranged from her adopted son.

There are many kinds of love that are rewarding. There is love of acting – a love which has comforted and consumed Barbara Stanwyck most of her life. Once when she was asked what she would do with her life if she were ever too old to act, she answered – only half in jest – “Well, they shoot horses when they’re through.”

Her love of acting has cost her both her marriages.

She was twenty-one years old when she married Frank Fay. He was a confident, cocksure Irishman with a measureless thirst and a golden tongue. He was a Broadway star. When they took the train to Hollywood in 1929 Frank Fay was the one the insiders counted on to become a movie star. Barbara had starred inn exactly one play. She was just another pretty girl trying to make good.

In Hollywood, she was almost an overnight success. Frank Fay was an overnight failure. She tried to ease his failure. She gave him loyalty, devotion and her money to invest. She adopted a baby in order to give him a son. She tried to hide her success from him, tried to pretend he was still the most important member of the marriage.

Frank Fay was a proud man. All her efforts to help only added to his sense of failure, because there was one thing she could not force herself to do. She could not give up her career for him – the one thing that might possibly have saved her marriage.

If her success was the indirect cause of her divorce from Frank Fay, her career was a direct cause of her divorce from Robert Taylor. They had been married nearly eleven years when Bob Taylor had to go to Rome for a year to star in “Quo Vadis.” He begged Barbara to go with him, but she couldn’t stand the idea of “doing nothing in Rome for a year” while he was working. “I’m not good at being idle,” she told him. “I don’t know how”

During that year in Rome, Taylor’s name was linked with the name of an Italian starlet. Shortly after his return to Hollywood, Barbara filed for divorce. “In the past two years,” she announced – with unintentional irony – “because of professional requirement, we have been separated just too often and too long.”

Out of the past

No one can live his life again, endowing the past with knowledge of the present. But if Barbara Stanwyck could once more be the twenty-one-year-old girl with the husband she adored, would she choose to live her life the same way? Would she choose to set her feet once more on the path that led to the destruction of two marriages?

Perhaps she herself does not really know.

However, Barbara has fully accepted, without attempting to deceive herself, her love of acting and it’s consequences. “Romance is a form of happiness, of course,” she says, “But I think I’ve given up on that. And turned to what I know best. To my work. That’s a form of happiness, too. Doing something well. Creating something.”

Lee Majors could learn from Barbara Stanwyck not only the kindness and generosity, the benevolence and devotion that is part of love. He could learn also that the passionate love between a man and a woman demands sacrifices that Barbara Stanwyck was unwilling or unable to make. He could learn that you cannot put your career, your ambitions or your desire to be a star ahead of your marriage without risking your marriage.

Lee Majors has already failed at marriage once. The marriage of Harvey Lee Yeary from Middlesboro Kentucky – population 14,482 – to the pretty high school girl he fancied never grew roots in the lush earth of Southern California. It withered, leaving behind it only Harvey Lee Yeary Jr.

Will he learn from the failure of his marriage? Or will he consider the death of love an unfortunate accident for which he bears no responsibility? Love can teach many lessons. Will Lee Majors ever learn any of them