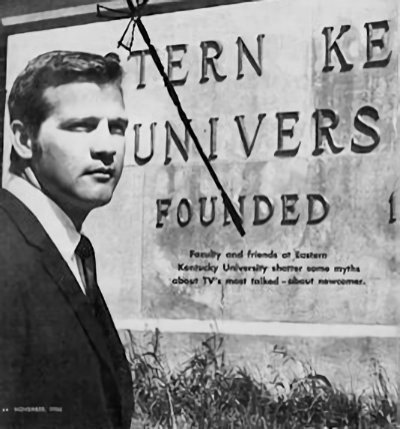

HOW THE CLASS OF ’63 REMEMBERS LEE MAJORS

Movie Life By Betty T. Balke – November 1966

Heath, the brooding Barkley of Big Valley, is completely out of character for Lee Majors. And much of what is written about Lee is pure, unadulterated “hokum.” So say the people who knew Harvey Lee Yeary of Middlesboro, Kentucky’s best, back in the college where he spent four eventful years of his life, not really so long ago.

Heath, the brooding Barkley of Big Valley, is completely out of character for Lee Majors. And much of what is written about Lee is pure, unadulterated “hokum.” So say the people who knew Harvey Lee Yeary of Middlesboro, Kentucky’s best, back in the college where he spent four eventful years of his life, not really so long ago.

Lee, far from being a moody, dour wanderer who just happened to stumble into acting, is remembered as “a very amusing fellow who always had a joke or two” … “a most outstanding athlete and natural leader”… “a superior student actor.”

Despite the way in which the real Lee Majors has somehow dissolved into image and myth, the people of his alma mater, Eastern Kentucky State College in Richmond, are delighted for him and tune in faithfully to Big Valley.

Nor has Lee forgotten Richmond; he has been back to visit some half-dozen times since his pilgrimage to Hollywood in 1963, the last time in May for the Kentucky Derby. He has remained unassuming, but of course people treat him differently now: he was the house guest of onetime college professor of his, and he attended the Derby not as an always-broke college boy, but as a celebrity. And through all, Lee remained unruffled and poised, a quality everyone who knows him has noted.

Lee’s critical years were spent at Eastern (now a university), where he enrolled in February 1959, and graduated, a certified teacher, in May 1963. Here he knew pain and frustration, and turned both into triumph. Here he stretched his mind, and developed what was already an athlete’s body into a stronger, tougher, faster physique. Here he courted a girl, and married her. But above all, here in Richmond, Harvey Lee Yeary made the decision and took the first difficult steps that were to lead him to Hollywood and the career of an actor.

It all began with football. “Harvey was a great high school athlete, and we tried real hard to get him,” recollected Glen Presnell, onetime All-American half-back (Nebraska) and head football coach at Eastern until he became Athletic Director, “But Harvey signed up at Indiana University.”

Apparently, Lee, a rather shy and reserved small-town boy, was bewildered by the vastness of faraway Indiana U., and it wasn’t long before he applied to Presnell for a football grant-in-aid at Eastern, so much closer to home. The record shows he enrolled as a transfer student and, following the NCAA rules waited a year before he could play on the varsity.

So, for that year, Lee worked out with the squad, and lived with the rest of the team in a dormitory room (one of a dozen or so) built underneath the college’s aging stadium.

“A great defensive end, fast and agile,” is the way Coach Presnell describes Lee, “and an excellent pass receiver.”

Finally, the big day dawned for Lee: September 17, 1960. The stands were packed, the fall sun shining, the Maroon band blaring the fight song of the team – including #81, Harvey Lee Yeary, End – trotted out onto the field for the opening kickoff. Opponents were Fort Campbell, an Army eleven from Northern Kentucky.

Lee didn’t have a chance.

Before he could catch a touchdown pass or do much of anything, there was a big pile-up on the field. On the bottom, with a seriously injured back was Lee. Mrs. Clyde Coleman, Athletic Secretary, recalls the concern of Lee’s parents, who came to see Coach Presnell about their son’s injury, and grieved with him that he couldn’t play the game he loved. “He was heartbroken, “Mrs. Coleman recalls, “And that he ever played again is a tribute to his willpower and determination in the face of the kind of injury that might have side-lined a lesser man for good.”

Mrs. Clyde Coleman, Athletic Secretary, recalls the concern of Lee’s parents, who came to see Coach Presnell about their son’s injury, and grieved with him that he couldn’t play the game he loved. “He was heartbroken, “Mrs. Coleman recalls, “And that he ever played again is a tribute to his willpower and determination in the face of the kind of injury that might have side-lined a lesser man for good.”

But Presnell’s hopes for Lee were kept alive with the kind of wait-‘til-next-year outlook necessary to a coach’s morale.

About this time Lee made a fateful decision.

He decided to follow his growing interest in drama. He would concentrate his senior year upon acting; furthermore, he would go about it in the same all-out, intense way he went about excelling at sports.

So, to preserve his handsome features from being ground into the turf and to save his muscular frame from broken bones, Lee reluctantly hung up his football jersey and resigned his grant-in-aid.

Coach Presnell understood, and wished him well.

Lee spent the summer in 1962 in Danville, Kentucky taking lessons in acting from Eben Henson, director of the Pioneer Playhouse there. Henson recalls that for “a month and a half” he gave Lee a two-hour acting lesson every day.

From his first meeting with Lee, Henson felt the lad was destined for stardom. “He was a leading-man type, and he had more drive and willingness to work than most.”

So Henson and Lee shook hands and arranged a deal, in which not a penny exchanged hands: in exchange for acting lessons, Majors would later appear in one of Henson’s outdoor theatre productions.

Henson found Majors an able performer. “Comedy is his forte,” he says, regretting that TV audiences, thus far, have not glimpsed that side of Lee’s acting.

George Proctor agrees.

George was Lee’s classmate when in the fall of 1962, Lee came back to Richmond from his summer in Danville and registered for his final semester of classes. Lee and George were both in Drama 262, otherwise known as “Fundamentals of Acting” taught by a new professor, Joe. M. Johnson.

“Harvey always had something funny to say, and I knew him as an amiable, good-natured fellow. We’d known each other before – he’d been a football player and I’d been manager of the college swimming team. So we teamed up in class for a number of two-man scenes.

“Sometimes we’d be doing an agonizing tragic scene in front of the class, and Harvey would get this very small twinkle in he eye – or I would – thinking of something funny, and then both of us would break up.”

By this time, Lee’s interest in acting was intense. Proctor found him willing to rehearse “anytime, anywhere.”

“We took our final examination together,” Proctor recalls. “You ask me what kind of student Harvey was? Well, he made an A. I made a B.” His movements were good; he had poise and confidence on stage, no matter what character he was playing. Proctor says, “I’m sure his athletic background had much to do with his ease of movement. I’ll just say what I say to my high-school acting students: athletic skills will help you in drama.”

When George saw Lee in his debut on the college stage, playing a character, by the way, named Proctor, he felt he was watching a man on his way to becoming a professional actor The play was Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, which played for a week in November, 1962, at the Eastern Little Theatre, Joe Johnson directing. Lee won the lead in an open audition. He played the demanding role of John Proctor, married to a cold, unresponsive woman, accused of being a witch in seventeen-century Salem.

The play was Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, which played for a week in November, 1962, at the Eastern Little Theatre, Joe Johnson directing. Lee won the lead in an open audition. He played the demanding role of John Proctor, married to a cold, unresponsive woman, accused of being a witch in seventeen-century Salem.

Proctor is on stage in almost every scene. He plays tender love scenes, weeps, loses his temper, and handles numerous props; a gun, a whip, food. Anybody who’s even had a walk-on in any high school play knows these things are hard to do, naturally and gracefully.

Director Joe Johnson was making his debut too. He had just joined Eastern’s faculty, and as intensely as Lee, he wanted this first college play to be a success.

“People came to see Harvey Yeary, the football player, and some of them came prepared to scoff,” admits a classmate of Yeary’s, now a high school math teacher. “But they stayed to applaud him, and went away praising him.”

What his audiences didn’t know was that for some eight weeks, ever since he had won the part, Lee had bent all his energies to the role.

“Yes, he’s good-looking and sensitive and agile in movements, “says Joe Johnston, “but what has made Lee succeed is his attitude. Once he got the part, he spent 6 to 8 hours, every day, seven days a week, getting ready for it.

As a result Lee had mastered his role by the time full-cast rehearsals began, and the play became, with its opening night, a kind of legend at Eastern. “It is a kind of touchstone,” says Johnson. “to which every play we have done since is invariably compared.

“There’s one especially tender scene in The Crucible,” Johnson recalls, “in which Lee says a last goodbye to his wife in prison. He was so immersed in the role that he cried – real tears – at every performance. Not many actors can cry on cue.”

Lee is what actors and directors call a “quick study,” learns his lines rapidly, grasps the overall meaning of the play in a hurry.

How has Lee changed?

Well, in the words of the people who know him best, “not much.” And those same people are pleased to have the record set straight, and the true story told of Harvey Lee Yeary’s days at Eastern Kentucky State College. And at Middlesboro before that, where Harvey was voted “Best Looking Boy” in his senior year at Middlesboro High and though somewhat reserved, was “very popular.”

Joe Johnson found Lee possessed of “more self-assurance” each time he returned to Richmond since settling in Hollywood. “But Lee always had a quiet kind of self-confidence that has nothing to do with conceit. I think maybe there’s an added maturity about him, too.” Johnson says.

He and Henson and Proctor – who look with a director’s objective eye on Lee – says he looks much the same, except that he is perhaps a little huskier than when was an undergraduate. Their practiced ears notice the lower-pitched voice, the result, they think, of training and effort. And the Kentucky twang has nearly disappeared from his speech off-camera, even though it’s natural on-camera, as the accent of Heath Barkley.

In anybody’s “Run for the Roses,” says Harvey Yeary’s old friends and classmates, Lee Majors is the one to bet on!